'We Built This City' uses visual and oral recorded histories ..

The contributions of Birmingham's Irish ..

An exhibition recording the contribution Irish workers made to the rebuilding of Birmingham in the post-war period has attracted record numbers of visitors to the city’s museum and art gallery.

"Building on success"

Featured Image: Fabian Cowan is lifted aloft by his friend Larry Miller while another friend takes their photograph as they worked on construction of the Marks & Spencer building in High Street. Photograph: courtesy of the Cowan family

The Background ..

Watch the video ..

A video using archive footage to accompany the exhibition can be viewed on YouTube. A souvenir newspaper recording the oral histories and photographs was also printed.

Extracts from stories by contributors ..

What follows are extracts from some of the stories told by contributors to the project, and photographs illustrating their experiences, reproduced by kind permission of the exhibition organisers and the photographers credited, or their representatives.

Featured Image: The late Fabian Cowan’s photograph of an Irish builder working without safety harness on the construction of a building in Birmingham city centre. Photograph: courtesy of the Cowan family

Carmel Girling, Writing about her father

"My father, Fabian Francis Xavier Cowan, was born in 1927 in Welsley Place, Dublin, the youngest of nine children in a family that had been well off in the Edwardian times but which had fallen on hard times. His mother Mary Cowan (nee Synott) had been home educated and was a teacher, whilst his father, James, was a fine carpenter and cabinet maker and is believed to have worked on the Titanic.

"Fabian had a good education, taught by Jesuit brothers at O'Connell's school on North Circular Road Dublin, and was a talented man able to play the piano with skill and indeed any instrument he could pick up. As a young man, before leaving Ireland, he did his national service with The Irish Army in the Engineers.

“He arrived in the city with a brown paper bag clutching his few clothes and little else. With no money or anywhere to stay, he slept rough on New Street railway station until he got a ‘sub’ (financial advance from wages) from his first job on the buildings.

“Why Fabian had a camera when he had little else was probably because he was from a creative family and he may have acquired it from one of his older brothers.

"The brothers were all fascinated by the developing media, taking pictures and experimenting turning black and white images into colour.

“Fabian himself turned any spare space into a dark room to develop his own images – these are just a few examples. Forgotten for four decades, rolls of negatives were found in a biscuit tin in the garden shed after he passed away in 2004.

The Spaghetti Junction ..

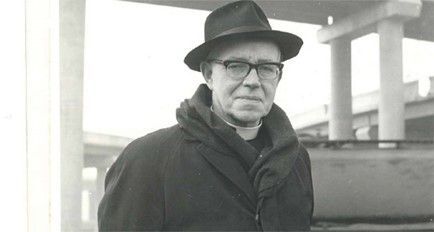

Father Dan Cummings (1907-1977)

-

Father Dan Cummings (1907-1977)

ButtonPhotograph: courtesy of Rosemary Doherty

-

Workers at Birmingham's Spaghetti Junction

ButtonPhotograph: courtesy of Brenden Farrell

-

Fr Dan Cummings (far right) wrote of this photograph 'All of these men are Irish'

ButtonPhotograph: courtesy of Rosemary Doherty

-

Fr Cummings wrote: 'They were very shy about posing for this picture'

ButtonPhotograph: courtesy of Rosemary Doherty

Enlarged Images: Click the links below to see images in a new window (in order of appearance above).

- Image one - click here

- Image two - click here

- Image three - click here

- Image four - click here

A long history of supporting people ..

Get in Touch ..

Search This Website: Use the search box (right) to look for content on this website. Type or speak the relevant words using the icons.